Last week PBS debuted an excellent documentary about legendary trumpet player Doc Severinsen, called "Never Too Late: The Doc Severinsen Story." Severinsen, whose 30 year stint as the musical director of the The Tonight Show With Johnny Carson made him a household name in America, is 93 years old and still going strong. It's a fascinating portrait of Severinsen the artist and Severinsen the man, well worth watching.

|

| Doc Severinsen |

If you asked a group of jazz buffs to name their top five favorite trumpet players, I'm pretty sure Severinsen's name would not be on anyone's list. I found one online list of "the best jazz trumpet players" that doesn't have him in the top 50. Most aficionados wouldn't consider Severinsen to be in the same league as trumpeters like Dizzy Gillespie, Clifford Brown, Lee Morgan, Kenny Dorham, or Freddie Hubbard -- not to mention Miles Davis.

But the comparison is fundamentally flawed. Severinsen was not a bebop trumpeter. Born in 1927, he came of age in the big band/swing era. He was a trumpet prodigy and played with the local high school band in Arlington, Oregon while still in grammar school. He won a statewide trumpet contest at age nine and auditioned for The Tommy Dorsey Band when he was 14. He didn't get the the job, but before finishing high school he was on the road with The Ted Fiorito Orchestra, and went on to play with big bands led by Charlie Barnet, Benny Goodman, and Tommy Dorsey, before landing a gig with the NBC studio orchestra in the 60s.

Severinsen represents a group of jazzmen who didn't make the transition from swing to bebop. They continued to play mainstream jazz -- touring with big bands or big band tribute groups, working in television, doing recording sessions, playing in Vegas show bands, teaching, and (at least in some cases), making jazz-pop albums that sold in the millions.

These musicians included names like Maynard Ferguson, Conte Candoli, Herb Alpert, Dick Hyman, Enoch Light, Acker Bilk, Andre Previn, Bobby Hackett, Pete Fountain, Al Hirt, and Skitch Henderson.

[A number of other performers, like Bob James, Gerald Wilson, Quincy Jones, Buddy Rich, Ramsey Lewis, Sergio Mendes, Wes Montgomery, Charlie Byrd, Shorty Rogers, George Benson, Bud Shank and the like, had feet in both camps.]

What these mainstream players had in common was that were extremely talented, well-respected musicians who didn't embrace (at least not fully) the improvisational style of bebop. Instead, they continued to play a more melodic jazz that appealed to their established audience of (mostly) white middle-class folks who had been raised on big band and swing. While most of the original mainstream jazzmen are gone, the genre continued to flourish, evolving into soul jazz, smooth jazz, and contemporary jazz, while spawning a new group of star performers such as Grover Washington, Jr., Chuck Mangione, David Benoit, Kenny G, David Sanborn, Diana Krall, John Scofield, and Chris Botti.

Like many things in America, there was a racial component in the division between mainstream jazz and bebop. Bebop was dominated by Black musicians and initially embraced by young urban audiences in largely African-American neighborhoods like Harlem (I'm simplifying here.) Much like rock 'n' roll 15 years later, bebop was initially considered to be decadent and a little salacious.

On the other hand, mainstream jazz was played by (mostly) white musicians and appealed to the white, middle class who were still listening to their big band albums. But beyond race, there was a fundamental question of musical taste; when it comes to the arts, people like what they like. And in the 1960s and 70s, middle class, middle-aged white Americans by and large didn't come home from work and put on The Sidewinder by Lee Morgan. Instead, they sipped a martini while listening to Al "He's The King" Hirt. The description on the cover of Hirt's 1963 hit album Honey In The Horn (above right) says it all: "Soft Trumpet - Sweet Voices."

|

| Honey In the Horn - Now That's More Like It |

It's really no different than popular taste in art or literature. People appreciated Saul Bellow, but they actually read Sidney Sheldon. They appreciated Picasso, but they had a Norman Rockwell print hanging in the living room. And when it comes to jazz, they appreciated Miles Davis, but they listened to Al Hirt and Herb Alpert. Which is exactly why you can find an album or two by Al Hirt or Herb Alpert for a buck in just about any thrift store in America; they sold millions of records. On the other hand, an original copy of Lee Morgan's The Sidewinder in top condition will set you back a thousand bucks -- if you can find one. And while Lee Morgan is more critically acclaimed than Al Hirt or Herb Alpert as a trumpeter, who can say if Morgan would have traded some acclaim for a gold record or two.

In my pandemic stupor, I recently ordered about 50 jazz albums from a Chicago record dealer. A few of the LPs I picked out were by mainstream jazz musicians, including one by Doc Severinsen, a 1980 title called The London Sessions (left). [I assume the title was an intentional shout out to the The London Howlin' Wolf Sessions (1971) and The London Chuck Berry Sessions (1972), but who knows.]

Severinsen's London Sessions LP was recorded at the fabled Olympic Studios in London's West End (as was The London Howlin' Wolf Sessions). The album was marketed as a limited edition, audiophile release with a numbered, gold foil stamp on the front cover (it looks blue in the photo). The session was an early digital recording, and much of the inside of the gatefold sleeve is taken up with a lengthy explanation of the the digital recording process. It includes a detailed list of the recording equipment used and a diagram of the studio, indicating the placement of all the instruments and microphones. While some of the track choices are questionable (including Rod Stewart's dreadful "Do Ya Think I'm Sexy?"), the overall sound is outstanding with a huge soundstage and wide dynamic range. And notwithstanding the blanket of strings that threaten to smother the listener with a layer of schmaltz, Severinsen's burnished tone and dynamic playing shine through on jazz-pop versions of Steely Dan's "Peg" and Leon Russell's "This Masquerade." It's a well-produced, nice-sounding album, but I won't be playing it with any regularity.

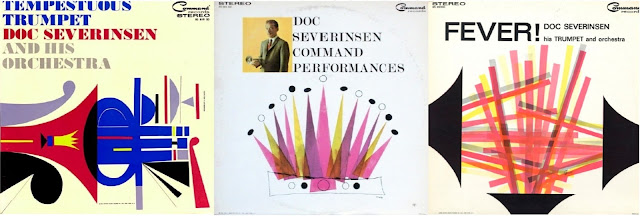

The only other Severinsen titles I own are three 1960s releases on the Command Performance label. Command Performance was started by musician and bandleader Enoch Light in 1959 as an audiophile label at the dawn of the stereo era. Early releases used exaggerated left-right separation to emphasize the wonder of the new two-channel technology. Many Command Performance albums featured distinctive artwork by artist Josef Albers, a pioneer of 20th century modernism (above). [Since you can often find Command Performance titles for a dollar or two, they're worth collecting for the cover art alone.]

Interestingly enough, there is a version of Lee Morgan's hit single "The Sidewinder" on Severinsen's 1966 release Fever! (above right). It's instructive to listen to Severensin's version side-by-side with Morgan's original, because it almost perfectly sums up the difference between bebop and mainstream jazz. Morgan's original version of the song is 10:28. It's an infectious soul-jazz classic that grooves and swings like crazy. It includes tasty solos by Morgan on trumpet, Joe Henderson on tenor, Barry Harris on piano, and Bob Cranshaw on bass. After ten minutes, you wish it would go on for another ten. Fabulous. I could listen to it every day.

Severinsen's version weighs in at 2:48. The band is hot, the song is upbeat and fun. But even though the liner notes describe how "Doc cuts loose in between the opening and closing riff," he really just throws in a few slides and trills to the basic melody, and before you know it, we're done. The band never strays from their charts. I haven't listened to the album in years.

I have at least two or three titles by most of the other mainstream jazz performers I listed above. I hardly ever listen to any of them. In fact, most have been consigned to overflow shelving in the garage.

Severinsen released his last recording in 2014, a Latin-themed collaboration with a group he heard playing in a club in Mexico. [The album is called Oblivion (left), and it's fun and catchy in a Gypsy Kings kind of way.] During his 70-year career, Severinsen has put out some 60 albums. I suspect that hardly anyone could name a single one. Not because they're bad, but because nearly every one of them features a selection of three-minute versions of (then) current pop hits, standards, and show tunes that never stray from the melody.

Don't get me wrong. I'm not down on Severinsen. He is a gifted trumpet player and performer who continued to draw large crowds well past his 90th birthday. He was one of the most popular and well-loved trumpet players of all time. But it would be hard to argue that he had much influence on the history of jazz music. Certainly not compared to the enormous impact of Dizzy Gillespie or Miles Davis. Jazz buffs don't discuss the nuances of Severinsen's style from album to album or study the interplay between him and his rhythm section. But that's OK, because not everyone has to advance the art. The world needs Saul Bellow and Sidney Sheldon.

Severinsen, Al Hirt, Pete Fountain, Maynard Ferguson, Herb Alpert, Andre Previn, and many other mainstream jazzmen had successful careers, made great music, sold a lot of albums, and brought musical pleasure to millions. That's not a bad epitaph for any musician.

Enjoy the Music!

No comments:

Post a Comment