I grew up in the 1960s and 70s, and my musical taste remains firmly entrenched in those decades. At least 90% of the 8,000 rock, pop, and jazz LPs in my collection were released during those 20 years. In fact, I have more albums released in the 50s than the 80s, 90s, or 2000s.

That's also why my car radio (infotainment unit?) is permanently tuned to Sirius XM Channel 26, a program known as "Classic Vinyl," whose tag line is "The most influential albums of the 60s and 70s." With only a handful of exceptions, I don't have much interest in artists or music from the last 40 years. That's not a reflection of the quality of the music or the performers of the last decades (well, maybe a little), it's just not the music I grew up with. And, as I wrote in a previous post, it's a scientific fact that nearly everyone's favorite music is whatever they listened to while going through puberty (yes, really).

As a result, I'm always pleasantly surprised to discover a new-to-me band or performer from this century that resonates with me musically. A couple that come to mind are Josh Rouse, a fabulously talented singer/songwriter in the tradition of John Gorka or Greg Brown, and The Explorers Club, who were, as near as I can tell, cloned in a laboratory to sound just like the Beach Boys. Of course, as you may have noticed, both Rouse and The Explorers Club have a classic pop sound that appeals to my antiquated taste.

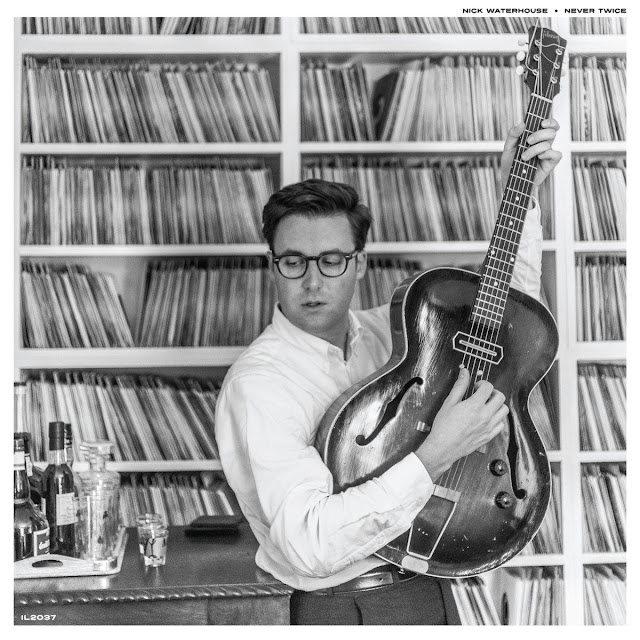

I mention all this because I recently came across a 2016 album by artist Nick Waterhouse called Never Twice (below). I had never heard of Waterhouse, but the cover -- with Waterhouse holding a vintage hollow-body electric guitar in front of a massive collection of 45s and a selection of booze -- looked intriguing, so I took a flyer. Great decision. I've been playing the album for a couple of weeks now and am smitten by Waterhouse's retro-cool style. There may yet be hope for popular music in the 21st century.

In AllMusic's review of the album, critic Andy Kellman catches Waterhouse's vibe perfectly when he notes that he is "Dedicated as ever to synthesizing and replicating R&B-rooted sounds of the 50s and early 60s . . . akin to a slinking, swampy fusion of Booker T. & the MGs and Henry Mancini." In other words, Waterhouse's music is right up my alley. The prowling organ and sassy horn section (including a fat baritone sax) is exactly the music I want to hear while sipping an icy gin and tonic in my listening chair.

What's most impressive about Waterhouse's sound is that while his style is definitely retro, it's not derivative -- Never Twice sounds like an honest-to-goodness, long-lost album from the 50s. The same can be said for Waterhouse himself. Although he has clearly been styled for the cover of the album, in other images he looks like he just stepped off the set of Leave It To Beaver (left).

Never Twice is a unique blend of rockabilly, R&B, jazz, and old-school soul that reminds you of just about everyone, but doesn't sound exactly like anyone. Leon Bridges' retro soul is cut from a very similar cloth, but while Bridges is a crooner in the Sam Cooke mode, Waterhouse is harder to pin down; his voice doesn't sound like anyone I can think of, but there is definitely a little bit of Dion DiMucci, with a shot of Buddy Holly on the side. [Fun fact, Waterhouse does a raucous duet called "Katchi" with Leon Bridges on Never Twice.]

After spinning Never Twice for several weeks, I've ordered a couple of Waterhouse's other albums. I'm looking forward to eventually hearing them all.

While we're on the subject, I've also recently been digging the music of new-to-me jazz artist Dave Burns. Burns was a talented trumpeter who cut only two albums as leader, both on the Vanguard label. The first was the self-titled Dave Burns, released in 1962, and the second was Warming Up! from 1964.

My first thought about the albums was: Wait, Vanguard put out jazz albums? Apparently so. Unbeknownst to me, The Vanguard Recording Society, which started as a classical label and subsequently became a major player in folk and pop, also produced a short-lived jazz series called the "Vanguard Jazz Showcase," which was helmed by the legendary producer and impresario John Hammond. (The small print in the logo below is hard to read, but says: "A High Fidelity Production Supervised by John Hammond."

Hammond only worked with Vanguard from 1953-57, but the Jazz Showcase series limped along until 1962. Over the course of nine years, Vanguard released some 24 Jazz Showcase LPs (the early discs were 10"). Among the performers were Ted Brown, Ruby Braff, Jo Jones, and Vic Dickerson. The 1962 release Dave Burns appears to be the last album in the series. [Warming Up! from 1964 was released by Vanguard, but by then they had dropped the Jazz Showcase logo.]

Trumpeter Dave Burns was born in Perth Amboy, NJ, and began performing with various local bands in the late 1930s and early 40s. Following a stint in the Army (where he played in a military band with James Moody), Burns hooked up with Dizzy Gillespie in 1946 and traveled with his group for the next three years. From 1949-50, Burns played with Duke Ellington, before joining James Moody's band for the next five years. In the mid and late 50s, Burns continued to gig around New York (including playing on numerous recording sessions for the likes of Dizzy Gillespie, James Moody, Art Taylor, Johnny Griffin, and Milt Jackson) while working on and off as an appliance salesman to help pay the rent. Finally, in 1962, Vanguard signed Burns to record his first album as a leader.

Trumpeter Dave Burns was born in Perth Amboy, NJ, and began performing with various local bands in the late 1930s and early 40s. Following a stint in the Army (where he played in a military band with James Moody), Burns hooked up with Dizzy Gillespie in 1946 and traveled with his group for the next three years. From 1949-50, Burns played with Duke Ellington, before joining James Moody's band for the next five years. In the mid and late 50s, Burns continued to gig around New York (including playing on numerous recording sessions for the likes of Dizzy Gillespie, James Moody, Art Taylor, Johnny Griffin, and Milt Jackson) while working on and off as an appliance salesman to help pay the rent. Finally, in 1962, Vanguard signed Burns to record his first album as a leader. The resulting album, Dave Burns, features Kenny Barron on piano, Herbie Morgan on tenor, Steve Davis on bass, and Edgar Bateman on drums. Burns wrote three of the seven tracks. The music is mostly straight ahead bebop, with fine solos by Burns, Morgan, and Barron. It's an excellent debut that allows Burns' to show off his understated but swinging style in a variety of settings. Downbeat magazine's review of the album notes: "It's a mystery why this man (Burns) was not given his own recording date before now. He is one of the really mature trumpeters in modern jazz." Downbeat goes on to praise Burns for avoiding the "excesses" of other young trumpeters.

Burns' second album, Warming Up!, from 1964, includes some heavier hitters, including Al Grey on trombone, Harold Mabern on Piano, Bobby Hutcherson on vibes, and Billy Mitchell on tenor. The more experienced lineup makes for a meatier and tighter session with some exquisite playing that showcases all of the performers. This should have been the album that launched Dave Burns into the first rank of trumpet players. Unfortunately for Burns, a bebop album on the Vanguard label was apparently so incongruous that most critics and jazz fans completely missed it. As a result, both LPs disappeared with barely a trace. Though Burns continued to be in demand as a session player (Discogs lists more than 200 credits stretching into the 2000s), his brief career as a leader was over. In the coming decades, Burns turned his attention more and more to teaching, becoming one of the most sought-after trumpet masters in the city. He died in 2009.

Since the albums sold so poorly, originals of Burns' two discs are hard to find. As of this writing, there is only one original copy of Warming Up! for sale on Discogs, listed as VG+ with a price of $300. There are a few listings for originals of Dave Burns, but the best is in only VG condition with a price of $135. Both of Burns' discs were reissued in Japan in 1990 by King Record Co., and a few copies of each are available in NM condition in the $40-50 range. Finally, there are mint 2001 Scorpio reissues available for around $20. They sound pretty good, so don't hesitate to grab those reissues.

Enjoy the music!

.jpg)