Once you have a modest collection of albums -- let's say five or six thousand -- including nearly every essential work by nearly every essential jazz and rock artist (at least the ones you like), what do you buy next?

As my collection has grown, I have reached a point where there aren't many gaps left to fill in my core collection. For my favorite groups, like the Beatles or The Beach Boys, that means I have just about every note they ever recorded, including obscure outtakes and live recordings, home demos, and newly-issued remasters. For other rock and jazz artists like The Rolling Stones and Miles Davis, I have copies of all the albums that I like. I am never going to buy a copy of Dirty Work or Bitches Brew by Miles Davis, because even if I owned them I'd never listen to them. (Ditto for Dylan's Knocked Out Loaded and Down In The Groove.) Of course, your mileage may vary.

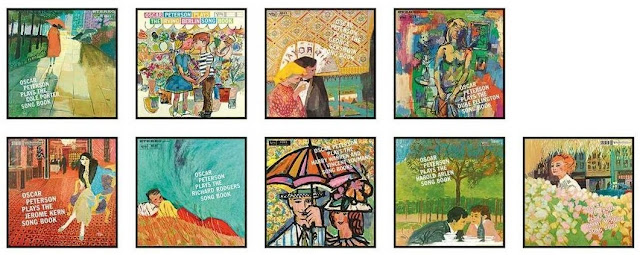

|

| Let's see: got it, got it, got it, got it, got it, got it, and got it. | |

Since there aren't a lot of essential recordings I'm still looking for, I've spent a lot of time in the last few years upgrading my collection: swapping out VG albums for Near Mint, buying newly-remastered audiophile releases to go with my original copies, or maybe picking up a first pressing to replace a latter reissue. But there is a limit to this as well, since continually buying the same album in the hopes of finding a slightly better sounding version is why I have eight (count 'em) copies of Steely Dan's Aja.

A more rewarding option is finding new artists that I somehow overlooked or missed the first time around. I've written about some of these in previous blogs - including singer songwriters like Jim Sullivan, John Stewart, and Tom Jans, all of whom I have really enjoyed listening to and learning more about.

When it comes to jazz artists, there are exponentially more talented and inventive musicians who I haven't really explored properly. For every Miles Davis, Dave Brubeck, John Coltrane, or Stan Getz (who between them probably sold 25% of all the jazz albums in the 50s and 60s) there are countless other brilliant players who toiled away in relative obscurity, gigging in clubs, hopping in and out of big bands, sitting in on other artists' sessions, or recording background music for TV shows and advertising jingles in Los Angeles and New York studios to make ends meet.

But thanks to a few discerning producers and a handful of intrepid record labels (who, let's face it, couldn't afford the big names anyway), some of these lesser know musicians occasionally got a chance to step into the spotlight and lead a session or two. And the resulting music is often every bit as compelling as anything the big names put out.

Lately I've been buying a lot of albums by these lesser-known artists on labels like Pablo, Concord Jazz, Pacific Jazz, Palo Alto Records, Chiaroscuro, Milestone, Muse, and Inner City. Some of the artists include Hampton Hawes, Joe Venuti, Frank Foster, Barry Harris, Al Cohn, Jimmy Raney, Zoot Sims, Ray Bryant, Red Rodney, Frank Wess, Ira Sullivan, Kenny Barron, Terry Gibbs, and Dolo Coker. And while they are far from unknown, none of these artists would be high on the list of top-selling or best-loved jazz musicians.

With that in mind, a few weeks ago I got an email from a record dealer in New York state saying that he had found a stash of new old stock (NOS) Xanadu Records from the 1970s and 80s, and did I want some? I had heard of Xanadu, but a quick check of my database showed that I didn't own any albums on the label. So I did a little research on the Interwebs.

|

| Don Schlitten |

Xanadu Records was founded by record executive/producer Don Schlitten. According to his Wikipedia bio, Schlitten was born in 1932. By 1955, at the tender age of 23, he co-founded his first record label, Signal, which recorded artists such as Duke Jordan, Gigi Gryce, and Red Rodney. When Savoy Records bought out Signal in the late 1950s, Schlitten spent most of the next decade working as a freelance producer, including leading a number of sessions for Prestige Records. Prestige eventually hired him as Vice President and Art Director in the late 60s. In 1972, he and fellow Prestige executive Joe Fields left the label to found Cobblestone Records, a small jazz imprint that released some quality Sonny Stitt LPs among its otherwise rather limited output. In the next few years, Schlitten and Fields went on to found Muse Records and Onyx Records.

In 1975, after Fields bought him out, Schlitten started his own label, Xanadu Records (inspired apparently by the name of the fictional mansion in Orsen Wells' film Citizen Kane, itself loosely based on newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst's palatial estate, Hearst Castle, in San Simeon, CA.) Over the next decade, Schlitten released more than 200 albums on the Xanadu label. The list of artists is a who's who of musicians that sound sort of familiar, but who you really can't place, including Al Cohn, Barry Harris, Charles McPherson, Mickey Tucker, Sam Most, Frank Butler, Ronnie Cuber, and Sam Noto.

In 1975, after Fields bought him out, Schlitten started his own label, Xanadu Records (inspired apparently by the name of the fictional mansion in Orsen Wells' film Citizen Kane, itself loosely based on newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst's palatial estate, Hearst Castle, in San Simeon, CA.) Over the next decade, Schlitten released more than 200 albums on the Xanadu label. The list of artists is a who's who of musicians that sound sort of familiar, but who you really can't place, including Al Cohn, Barry Harris, Charles McPherson, Mickey Tucker, Sam Most, Frank Butler, Ronnie Cuber, and Sam Noto.

Schlitten seems to have taken inspiration from Norman Granz's Pablo label (founded two years earlier, in 1973), in that he focused on straight ahead bebop, using a stable of in-house musicians who often played on each others' sessions and toured together. Just like Granz did for his Pablo releases, Schlitten took the pictures and designed the covers for his Xanadu albums. Both labels featured stark black and white cover photos taken in the studio during the recording sessions. And not to get too carried away, but also like Granz, Schlitten wrote many of the liner notes for his albums.

After some research, I picked out 10 Xanadu titles that looked promising and sent in my order. I received the records a few days ago, and while I haven't listened to all of them yet, so far I can say that these are extremely well recorded albums with great performances. And since they are original stock from the 70s and 80s, they are all-analog pressings. Of the ones I've opened, all but one were cut by Joe Brescio at The Master Cutting Room in NYC. (The other was mastered by John Matousek at Bell Sound Studios, NYC.) The sound on all of them is superb.

It's always a treat to discover great music by previously unfamiliar artists. I've still got a few albums to go, but so far the releases by trumpeter Sam Noto have been by a huge revelation for me. Based on some enthusiastic online reviews, I took a flyer and bought all four of his Xanadu albums, released between 1975-78. I am pretty sure I had never heard of Noto before buying these albums. Talk about your journeyman jazz players. The excellent liner notes on Noto's debut album, Entrance! (Xanadu 103), tell the story of a trumpet prodigy from Buffalo, NY, who at 14 years of age had his mind blown by recordings of Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker. He dropped out of high school and spent most of the 50s and 60s picking up gigs and traveling with a succession of big bands, including stints with Louis Belson, Stan Kenton, and Count Basie. In 1969, he moved to Las Vegas where he played in show bands so he could earn a steady pay check to support his family. It wasn't until 1975, when Noto was 45 years old, that he finally got his big break: After years of cajoling, the great trumpeter Red Rodney, who had heard Noto play in Vegas, finally convinced his old friend Don Schlitten, who just happened to have a brand new record label, to get Noto in the studio to record his first album.

The rest of course is history, as Noto went on to become the biggest-selling trumpeter in jazz history. Yeah, right. I don't know how many albums Noto sold, but I know it wasn't nearly as many as he deserved to. Which is a crying shame, because as music writer Phil Nyhuis points out in this excellent portrait of Noto: "Like Clifford Brown, one of his inspirations, Noto's jazz solos possess effortless technical mastery, a flawless sense of time, an endless supply of musical ideas, and a haunting, burnished sound." As of this writing, Noto is happily still with us and living in Buffalo.

The moral of the story is that no matter how many records you have, there is almost no end of wonderful music left to discover. If you're looking for some compelling hard bop played with style and substance, check out Sam Noto and Xanadu Records.

Enjoy the music!

I once had dinner with Frank Sinatra. Well, sort of.

I once had dinner with Frank Sinatra. Well, sort of.