As my collection has grown, I have reached a point where there aren't many gaps left to fill in my core collection. For my favorite groups, like the Beatles or The Beach Boys, that means I have just about every note they ever recorded, including obscure outtakes and live recordings, home demos, and newly-issued remasters. For other rock and jazz artists like The Rolling Stones and Miles Davis, I have copies of all the albums that I like. I am never going to buy a copy of Dirty Work or Bitches Brew by Miles Davis, because even if I owned them I'd never listen to them. (Ditto for Dylan's Knocked Out Loaded and Down In The Groove.) Of course, your mileage may vary.

| |

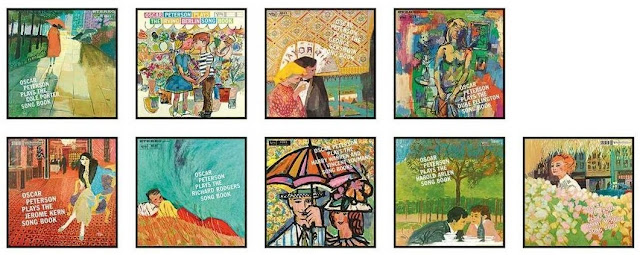

| Let's see: got it, got it, got it, got it, got it, got it, and got it. |

Since there aren't a lot of essential recordings I'm still looking for, I've spent a lot of time in the last few years upgrading my collection: swapping out VG albums for Near Mint, buying newly-remastered audiophile releases to go with my original copies, or maybe picking up a first pressing to replace a latter reissue. But there is a limit to this as well, since continually buying the same album in the hopes of finding a slightly better sounding version is why I have eight (count 'em) copies of Steely Dan's Aja.

A more rewarding option is finding new artists that I somehow overlooked or missed the first time around. I've written about some of these in previous blogs - including singer songwriters like Jim Sullivan, John Stewart, and Tom Jans, all of whom I have really enjoyed listening to and learning more about.

When it comes to jazz artists, there are exponentially more talented and inventive musicians who I haven't really explored properly. For every Miles Davis, Dave Brubeck, John Coltrane, or Stan Getz (who between them probably sold 25% of all the jazz albums in the 50s and 60s) there are countless other brilliant players who toiled away in relative obscurity, gigging in clubs, hopping in and out of big bands, sitting in on other artists' sessions, or recording background music for TV shows and advertising jingles in Los Angeles and New York studios to make ends meet.

But thanks to a few discerning producers and a handful of intrepid record labels (who, let's face it, couldn't afford the big names anyway), some of these lesser know musicians occasionally got a chance to step into the spotlight and lead a session or two. And the resulting music is often every bit as compelling as anything the big names put out.

Lately I've been buying a lot of albums by these lesser-known artists on labels like Pablo, Concord Jazz, Pacific Jazz, Palo Alto Records, Chiaroscuro, Milestone, Muse, and Inner City. Some of the artists include Hampton Hawes, Joe Venuti, Frank Foster, Barry Harris, Al Cohn, Jimmy Raney, Zoot Sims, Ray Bryant, Red Rodney, Frank Wess, Ira Sullivan, Kenny Barron, Terry Gibbs, and Dolo Coker. And while they are far from unknown, none of these artists would be high on the list of top-selling or best-loved jazz musicians.

With that in mind, a few weeks ago I got an email from a record dealer in New York state saying that he had found a stash of new old stock (NOS) Xanadu Records from the 1970s and 80s, and did I want some? I had heard of Xanadu, but a quick check of my database showed that I didn't own any albums on the label. So I did a little research on the Interwebs.

|

| Don Schlitten |

In 1975, after Fields bought him out, Schlitten started his own label, Xanadu Records (inspired apparently by the name of the fictional mansion in Orsen Wells' film Citizen Kane, itself loosely based on newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst's palatial estate, Hearst Castle, in San Simeon, CA.) Over the next decade, Schlitten released more than 200 albums on the Xanadu label. The list of artists is a who's who of musicians that sound sort of familiar, but who you really can't place, including Al Cohn, Barry Harris, Charles McPherson, Mickey Tucker, Sam Most, Frank Butler, Ronnie Cuber, and Sam Noto.

In 1975, after Fields bought him out, Schlitten started his own label, Xanadu Records (inspired apparently by the name of the fictional mansion in Orsen Wells' film Citizen Kane, itself loosely based on newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst's palatial estate, Hearst Castle, in San Simeon, CA.) Over the next decade, Schlitten released more than 200 albums on the Xanadu label. The list of artists is a who's who of musicians that sound sort of familiar, but who you really can't place, including Al Cohn, Barry Harris, Charles McPherson, Mickey Tucker, Sam Most, Frank Butler, Ronnie Cuber, and Sam Noto.Schlitten seems to have taken inspiration from Norman Granz's Pablo label (founded two years earlier, in 1973), in that he focused on straight ahead bebop, using a stable of in-house musicians who often played on each others' sessions and toured together. Just like Granz did for his Pablo releases, Schlitten took the pictures and designed the covers for his Xanadu albums. Both labels featured stark black and white cover photos taken in the studio during the recording sessions. And not to get too carried away, but also like Granz, Schlitten wrote many of the liner notes for his albums.

After some research, I picked out 10 Xanadu titles that looked promising and sent in my order. I received the records a few days ago, and while I haven't listened to all of them yet, so far I can say that these are extremely well recorded albums with great performances. And since they are original stock from the 70s and 80s, they are all-analog pressings. Of the ones I've opened, all but one were cut by Joe Brescio at The Master Cutting Room in NYC. (The other was mastered by John Matousek at Bell Sound Studios, NYC.) The sound on all of them is superb.

The moral of the story is that no matter how many records you have, there is almost no end of wonderful music left to discover. If you're looking for some compelling hard bop played with style and substance, check out Sam Noto and Xanadu Records.

Enjoy the music!